Lorde has a lukewarm relationship with the press. Her opinions alienate her from a large following and reward her with a cult one. Now, she says she loves the White Lotus incest storyline, “Bring the teeth! Freak us out!” Responses to the post shun her for “Normalising incest”. Lately, fiction has been met with similar phrases. “Stop normalising age gap relationships,” a popular one and on November 21, when Netflix unveiled a clip of the film, The Herd, there was a “Stop normalising tribalism” rebuttal.

The Herd (2025) by Daniel Etim Effiong tells a wedding celebration turned survival nightmare when the newlyweds and their best man are kidnapped by bandits. It is a comment on the current insecurity issues that Nigeria faces. However, it doesn’t follow a roman-à-clef route; it instead opts for a fictional one with a somewhat fairytale ending. Its lack of a pessimistic finale doesn’t unease the audience who choose to yell boo! Their main gripe is actually the use of Northern Nigerian muslims as the terrorists. While the movie starts with a disclaimer against tribalism, it is still interpreted as a direct jab at them. As a growing stereotype parrotted is the infamous kidnappers and herdsmen of the Hausa and Fulani tribe, native to the North. Like all stereotypes, it has its roots, this being that survivors of these inane attacks often recognise the language of the assailants as Fula.

Read more on survivors of herdsmen attacks: Surviving and Helping Benue: A Tiv Woman’s Tale.

The muslim stereotype stems from the attacks on churches in Nigeria, and the malignant terrorist organisation, Boko Haram, that has plagued Nigerians. The belief has become unshakeable, and Netflix normalised it? No. It depicted it, and that is what fiction has always done: Reflected the sign of the times.

Fiction as the zeitgeist reflection before The Herd

“One thing that people are all disturbed about is sex… That’s how I am going to attack the audience. I’m going to attack them sexually, and I am not going to go after the women in the audience. I’m going to attack the men. And I’m gonna put every image I can think of that I know will make the men in the audience cross their legs.” The words spoken by screenwriter Dan O’Bannon. He is talking about his hit movie, directed by Ridley Scott, Alien. The movie uses an alien specimen as a metaphor for human fears, and at the centre is one often associated with women— the loss of bodily autonomy.

Alien premiered in 1979, and O’Bannon no doubt had witnessed the 1973 court case of Roe V.Wade, a constitutional protected right of the United States to have an abortion (overturned in 2022). So his writing of a script where an alien forces a male character to birth an alien’s child (the single survivor is a woman) is no coincidence. It is uncomfortable, a metaphor for having to bear your attackers’ spawn, but that’s what people stood up to support.

Across the Atlantic, in Nigeria, the movies discussed tales of freedom, sometimes financial. These echo the spirit of the post-colonial and post-Civil War nation. In history, we see this in the rise of Gothic horrors, which, over time, evolved into science fiction. It showed a shift from the fear of mystical forces to that of technology, another fear that returned with the invention of cell phones.

In 2019, a research by Bo McCready examined the popularity of different film genres across the decades, and his statistical analysis gives us an interesting window into the national mood of the United States.

These films are written solely for “storytelling and awareness”, as Netflix puts it. They serve as fictional substitutes for the real stories and real people. A possible tool for propaganda or inspiration for people who actually might not want to be on camera, as this is a physical representation of their lowest moments.

Should uncomfortable depictions in fiction exist

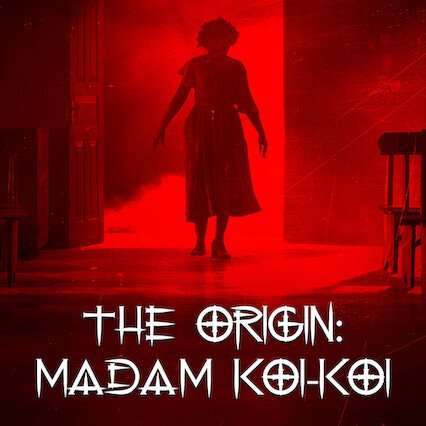

The Herd is not the first Nigerian (in recent times) to give the viewers an uncanny valley feeling. In 2023, Netflix debuted a limited series, The Origin: Madame Koi Koi, which explored sexual assault and rape in schools and the workforce. It was met with backlash for having a graphic rape scene and introduced a million impressions question: Why should rape scenes exist in film?

Horror movies, slashers, have been undeniably guilty of using or implying sexual assault scenes of women to titillate viewers. But for the most films, it serves as a time capsule of people. In his class on Narrative economics, the Nobel Memorial Prize for Economics winner, Robert J. Shiller, expresses, “It’s very rare these days to see a popular song about the stock market; it’s a sign that something was invading people’s thinking.” He is talking about the infectious tune that was the 1929 Eddie Cantor song, I Faw Down an’ Go Boom, which highlighted the instability of the stock market, which crashed 10 months after the song.

Nigeria has large reports of rape and sexual assault, and its National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reports that the number of female victims of rape in Nigeria increased from 48 per cent in 2021 to 65 per cent in 2022. With these numbers, it is fascinating that Nigeria hasn’t had a handful of high-budget shows depicting this. Almost akin to the Victorian belief that just because something happens doesn’t mean we should talk about it.

The decision of whether these should be graphic or otherwise falls into the hands of the viewer, except that the government has banned them. Adults do find it off-putting to insist they shouldn’t do something because you don’t like it.

Read more about the misleading assumptions on True Crime and why Abuja is a great True Crime destination

But the idea that movies shouldn’t depict real-life subjects because media-created translates to endorsement is a shallow angle, especially in an age of social advocacy.

Why does depiction strike a chord with viewers:

Simply put, Art does affect the human psyche. This phenomenon can be seen in the surge in interest in studying Law in the 2000s. In 2023, Legal Futures reported on a survey that half of UK law firm staff believe TV legal dramas influenced their career choice.

Another example is the FBI assisting with script reviewing and cast training for “The Silence of the Lambs” to depict gender biases in the criminology world. It also hoped to inspire women to join their workforce; it worked, or at least the FBI said so… even they didn’t predict the blockbuster it’d become.

A more fun and recent example would be the popularity of girls named “Bella” on TikTok. Their births often fall between 2008 and 2010, coincidentally with the hit film franchise, Twilight, whose female lead was called Bella.

Art depictions have also been proven to have a negative impact.

In 1981, the Journal of Research in Personality published an experiment by Neil M Malamuth. This saw Malamuth oversee 271 male and female students as subjects on the effects of exposure to films that portray sexual violence as having positive consequences.

The conditions of the research, specifically the type of stimuli (films), the “dosage levels” of exposure, and the duration of the effects, were discussed in relation to future studies and the broader social climate that promotes sexist ideology.

It saw a conclusion that exposure to films with violent sexuality significantly increased male subjects’ acceptance of violence against women, while the effects on females tended toward the opposite direction (less acceptance).

With art’s ability to inspire and influence its viewers, there is insight into why there’s a disdain for depictions of darker and sensitive subjects like The Herd and Madame Koi Koi.

However, The Herd does a decent job at centring fears and stereotypes; the clanish Igbos, the corrupt Yorubas, and the Muslim Hausa herdsmen. It unintentionally spotlights a rhetoric. How can you combat these fears when you don’t even want to see or acknowledge them?