Growing up, we never really listened to Fela at home, but I could recognise his music on the radio stations. Whenever “water no get enemy” would play as an accessory to a radio jingle on Capital FM, I remember my dad bobbing his head, finger tapping on the steering wheel, and saying in a voice laced with nostalgia, “Egwu Fela,” meaning “Fela’s Music”.

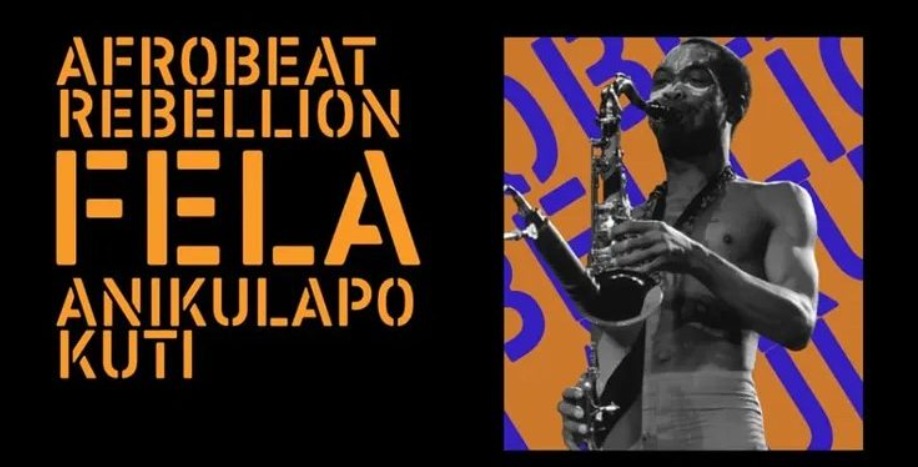

There were several exhibitions in Lagos this year, and there is a tendency to feel left out if you didn’t either host or attend one. Fela’s Afrobeat Rebellion was one of the exhibitions staring me in the face on my commute to and from work. The larger-than-life banner for Afrobeat Rebellion, 12th October – 28th December at the Eco Bank Pan African Centre, taunted me every day until I decided to see it.

When my dad spoke about Fela, he described him as a man who never feared the authorities and was essentially a government unto himself. He explained that Kalakuta Republic (Fela’s home) operated outside the government and society’s definition of order. In describing Fela’s previous home, he says, “It was an almost lawless place. Fela smoked a lot of marijuana and had a lot of women around in the compound. It was located at a prime spot close to Ojuelegba Junction, and you could catch buses from there to Lawanson, Idi Araba, and Yaba. Whenever the military raided, they ended up taking innocent people as well because of its proximity to the bus stop.”

True to his description, the original Kalakuta Republic was located at 14 Agege Motor Road, Idi-Oro, Mushin. That version of Kalakut –half-myth, half-warnings– is the one many older Nigerians still carry in mind. For the younger generation, however, what we have are these stories and curated experiences presented to us.

In contrast, the exhibition reception space greets you with an air-conditioned atmosphere, perfectly arranged decor, a painted zinc sheet stamped with Fela motifs, and Afrobeat Rebellion written on it. Stepping into the first room, we are introduced to a summary of the man, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, and his family. Yellow-orange hues on a black wall dominate the dimly lit area behind the entry curtain. With photographs and paragraphs neatly framed, the scene is nothing like the chaos we see in pictures and internet archives. This isn’t Kalakuta. This is safer, controlled, and curated, and I liked it.

WHO IS FELA ANIKULAPO-KUTI?

Although we see the current Afrobeats scene is dominated by acts like Wizkid, Rema, Ayra Starr, Burna Boy, and Tems, before the artists, there was the genre. Fela is widely regarded as the pioneer and principal innovator of the Afrobeats genre.

Read how to remake Ayra Starr’s viral makeup look.

Born in 1938 to a Clergy father and activist mother, he says in an unreleased 1967 Voice of America interview with host Sean Kelly that his parents urged him to learn the piano at age nine. He ran from it at first, but truly began playing at 14.

Interestingly, the Ransome-Kuti family was a prominent one in pre-colonial Nigeria, and Fela was what you could call a “nepo baby” in current slang. His paternal grandfather, Josiah Ransome-Kuti, an Anglican clergyman, was the first Nigerian to record a song on vinyl tape. His mother, Mrs Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, was one of the foremost precolonial feminists, and his father, Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, was an Anglican minister, school principal, and the first president of the Nigeria Union of Teachers. He was also a first cousin of Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka.

FELA AS A CURATED EXPERIENCE

The exhibition structures his life into ‘rooms’. The entry room presents a summary of the legend and his family, and this leads into a second room, which expands on the Ransome-Kuti Family. Here, it is less about Fela and more about the family that birthed him.

This is where I experience the auditory parts of the exhibition along with the visuals. An entire wall is dedicated to pictures, video clips, and newspaper cuttings of his mother and her activism. Certain sections of the room had headphone audio guides that walked visitors through the events and themes portrayed. Next to the wall where the family tree was drawn, headphones tucked into a groove played Pa Josiah’s recorded hymn. The sound was reminiscent of early 1920s records—audio punctuated with the scratchy sound of the gramophone, and audiostatic. In the modern display, listening back provided a sort of immersive historical experience.

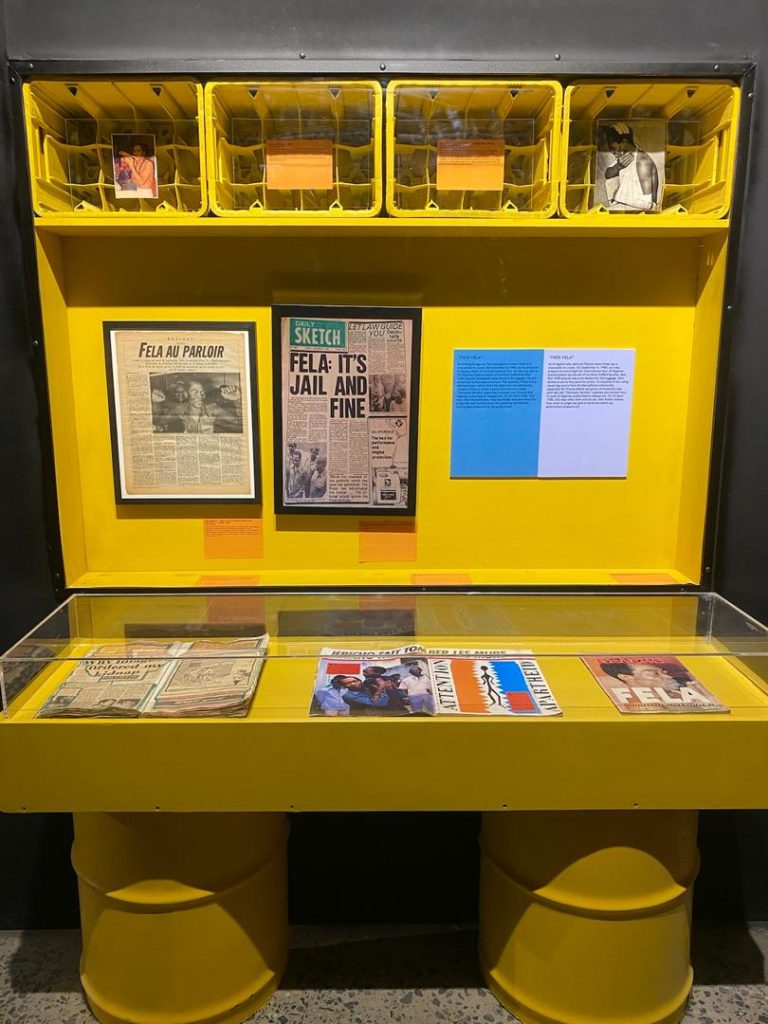

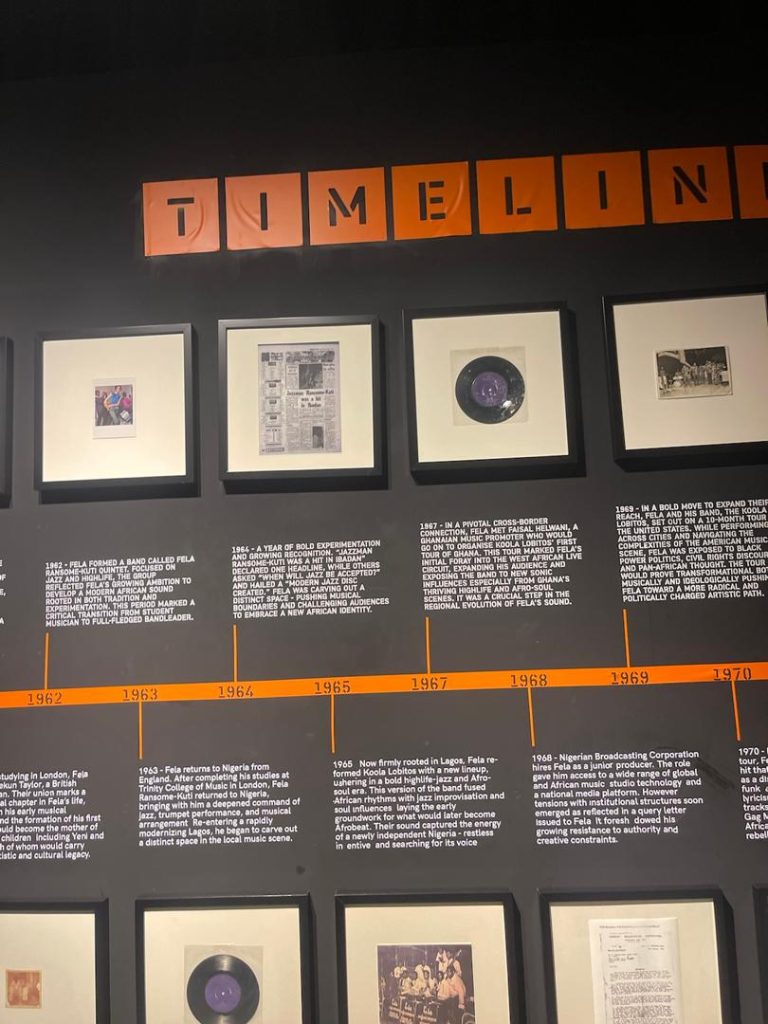

Beside this wall is a timeline of Fela’s adult life and musical journey: album releases with the actual vinyl tapes framed, newspaper cutouts corresponding to various eras of his band’s evolution, and pictures from landmark moments of his adult life.

It was in this room that I first heard the unreleased Voice of America interview. A guest who entered around the same time as I did presses one of the exhibition headphones to his ear and says to his friend, “He mixed jazz with highlife to create Afrobeat, and he sounds really young.” Both linger listening a while longer and move on to the next section, leaving the headphones behind, and I pick them up.

The interviewer calls him “Faylah” and asks, “What would you say is the present jazz scene in West Africa?” Fela’s voice is textured and laid-back, but at the same time, you can hear his enthusiasm when he answers the questions he is asked.

Drawing the curtain to the third room reveals a large screen playing snippets of Fela’s performances and carts containing his vinyl tapes. On screen, I recognise his 1978 Berlin performance with Africa 70 “Pansa Pansa”. This exhibit is mostly a sensory experience of his music and some of his performances.

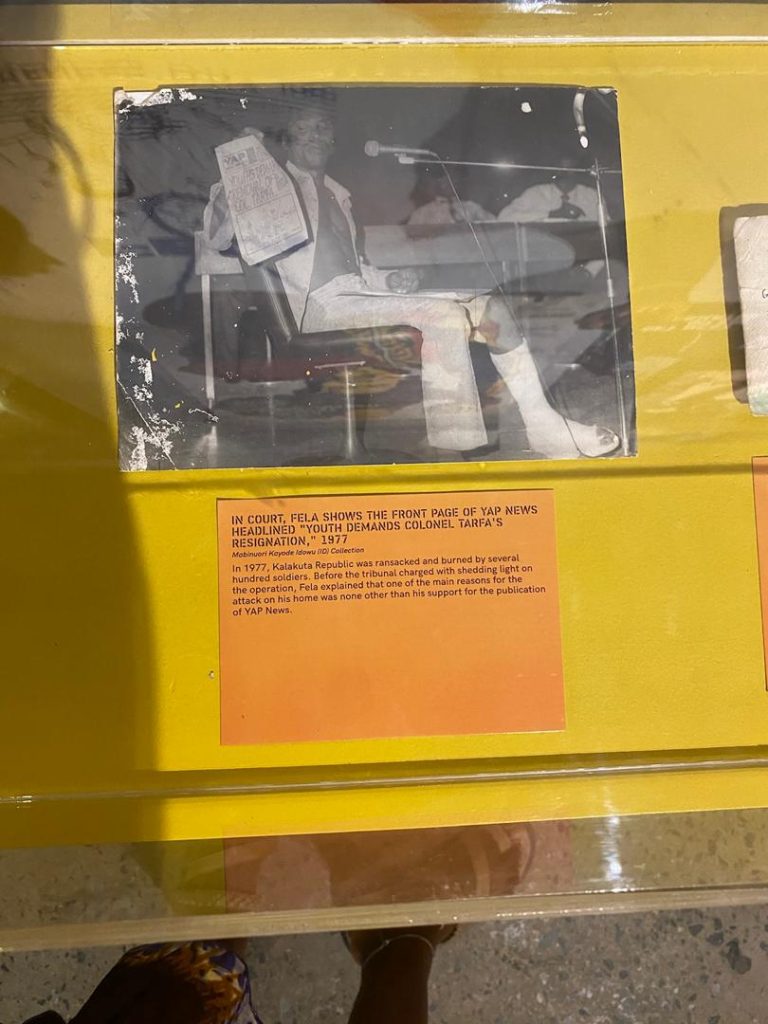

A fourth room reveals information about the Young African Pioneers (YAP) and Fela through the eyes of Lemi Ghariokwu, one of Fela’s main graphic designers. YAP was a youth movement founded by Fela in 1970 to mobilise and educate young Nigerians against social and political oppression. It served as a predecessor to Fela’s political party, Movement of the People, where he eventually decided to run for president. Here we see pictures and cover art by Lemi alongside YAP materials on display. Lemi, who was one of the pioneer members of YAP, also designed the membership cards.

Snippets of Fela’s activism and its fallout are captured here. Right next to the YAP display is an LED screen showing an interview with him.

In the video, Fela is seated in an armchair in his sitting room, wearing just briefs. Three women flank him, with the one to his far right puffing on a cigarette, and he picks up a lighter to light his smoke. He is speaking about the inspiration for his song, shuffering and shmiling, how the average African man likes to smile even while suffering. Between puffs, he discusses his motivations and intentions for his political party, Movement of the People. “Once there is one good government in any African country, all other countries thrive.” The clip cuts to him speaking on the beatings he had to endure by the Nigerian government during the raid, gesturing to show the camera bruises he incurred, “I want to show you.”

In a typical morals-be-damned manner, he pulls down his briefs to show us injuries on his bottom as well: “You must see it. Look my yansh. They beat me top to bottom, but I can’t die. My name is Anikulapo. I have death in my pouch.”

I am not watching this alone; I have company, and I catch her looking awed and horrified at the screen. R (26) says between laughs, “I can’t believe he actually pulled down his pants.” We are both observing this legend of a man, and although we’ve heard stories—as cohorts from the same generation—watching him generates a sort of shock value that is best experienced.

HOW DO YOU EXPLAIN REBELLION TO A CHILD?

The Afro Rebellion exhibition also curated an experience for younger audiences, which they termed “Young Rebels’ corner.” I encounter a small group looking at the newspaper clippings of the raid on Kalakuta as their tour guide explains some of the exhibits to them. A child exclaims, “Fela’s house got burnt! Did this actually happen? Why?”

Their guide explains that it was because he was an activist. I watched the children question, misinterpret, and absorb Fela Kuti’s legacy through simplified answers. It is impressive how the organisers chose to translate dissent to its youngest generation. Their curiosity adds a surprisingly tender counterpoint to the intensity of the room I just left.

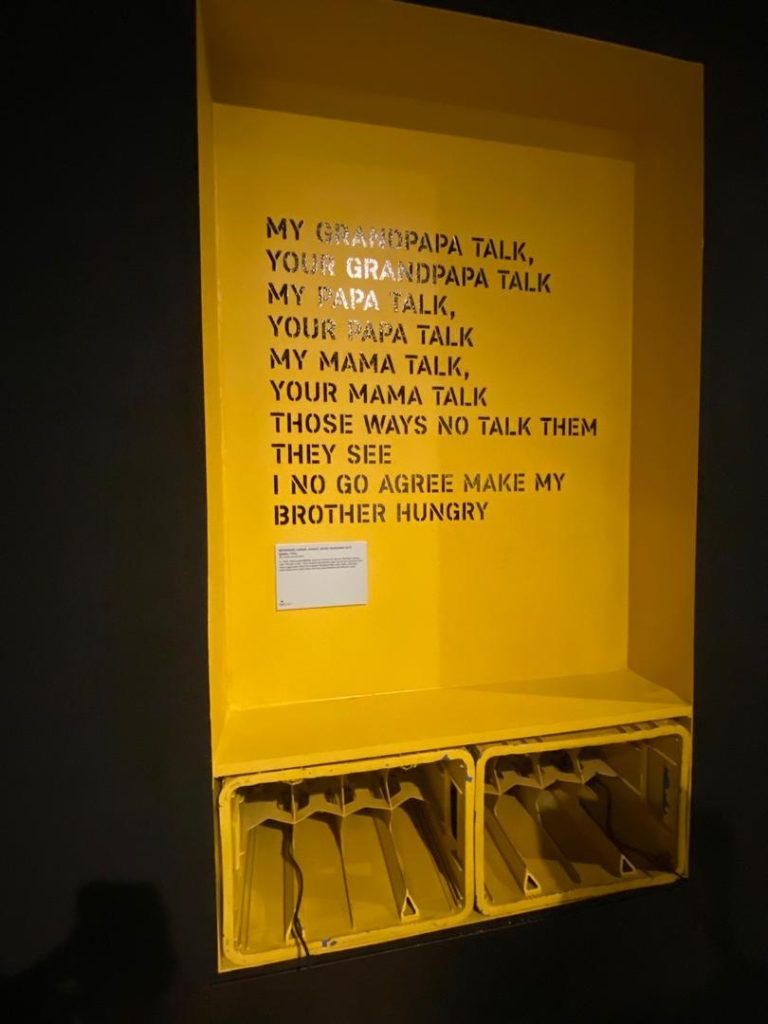

Another child asks,” Why was Fela in and out of jail? They said he stole money, did he steal money?” while another confidently answers, “They did it cause they were jealous. They just wanted to get him arrested because they didn’t like him”. This draws chuckles from the adults around. The ‘they’ in this case is the Nigerian government. Even as young as they were, they understood the basic premise of prejudice and bullying from the government, shaping a national figure into a story they could process. Fela’s commune, Kalakuta Republic, was violently raided and burnt down by the Nigerian military in 1977 after he released the song “Zombie”, which mocked the armed forces. The then-military junta had ransacked Fela’s compound. In the ruckus, his elderly mother, Mrs Fumilayo, was thrown out of the window and died from complications due to injuries she suffered. One might argue that simplifying the explanation weakens the story, but for the sake of the present audience, simplification is what they needed to connect the dots. The exhibition served as a fun lesson in history for childish curiosity.

HISTORY BECOMES AESTHETICS

Fela’s “let’s start” became a trending sound in TikTok videos with 69,180 total TikTok creators using the sound in the past three months, not counting its use on Instagram, according to data by Chartex. Since the Covid-19 era, TikTok has become both a launchpad for new artists and a gateway for rediscovering older ones. This creates a sort of musical bridge between the generations, where songs can be used to fit particular moods. In some corners, rather than a political figure or a musician with decades of ideological weight, Fela is regarded as a vibe for the moment.

The champions of this aesthetic music trend are the Gen Z digital natives, and exhibitions are the perfect venues to curate aesthetic Instagram photos. This is evident from the many times the camera flashes went off and the muttered “sorries” as guests tried not to interrupt each other’s photos and videos.

This is neither disrespectful nor surprising. It is simply the cultural moment we live in, akin to knowing the hook of a song but not the history behind it, knowing the iconography but not the ideology, filtering the past through the language of content.

Raxie (26), an exhibition attendee like me, wasn’t a fan, nor did she listen to his music outside the sound on social media, but his family members were. He chose to come mainly for the aesthetics. “My dad and brother liked Fela, and I wanted to know why. So I’ve seen it now, and I like him; he is my type of rebel.”

Jerry (23), in between his photos, said he had heard stories about him from his father, “My dad said you needed a visa to enter the original Kalakuta republic because Fela said it was independent from Nigeria.” As a fact, Fela did declare Kalakuta independent from the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

If the children were trying to understand Fela, this group seemed to be trying to experience him in their own way, and strangely, it mirrors Fela’s own complexity. He was spectacle, substance, noise, and meaning all in one. The exhibition forces you to confront both, even if many visitors only walk away with the part that photographs well.

FASHION, THE ICON AND HIS QUEENS

In an Instagram post, Chude Jideonwo mentioned how he saw Fela’s ‘pant’ on display at Afro Rebellion. For West Africans, Pant does not refer to the outfit trousers, but the underwear beneath the clothes, and indeed the Star’s undergarments were not excluded from the exhibition. Among the collection on display was a Barney-themed set, and it is difficult to imagine him in Barney briefs.

Fela’s decision to wear underwear publicly served as a political statement to show his aversion to “white man’s” social order. For him, wearing what was considered African clothing was a matter of staying true to his roots as he croons in his song Gentleman, “I be Africa man original.” While it is tempting to conclude that he never wore clothes from his home interviews, his wardrobe on display and his outfits during performances suggest otherwise, featuring tailored jackets and trousers in multiple shades, sporting intricate hand-embroidered designs.

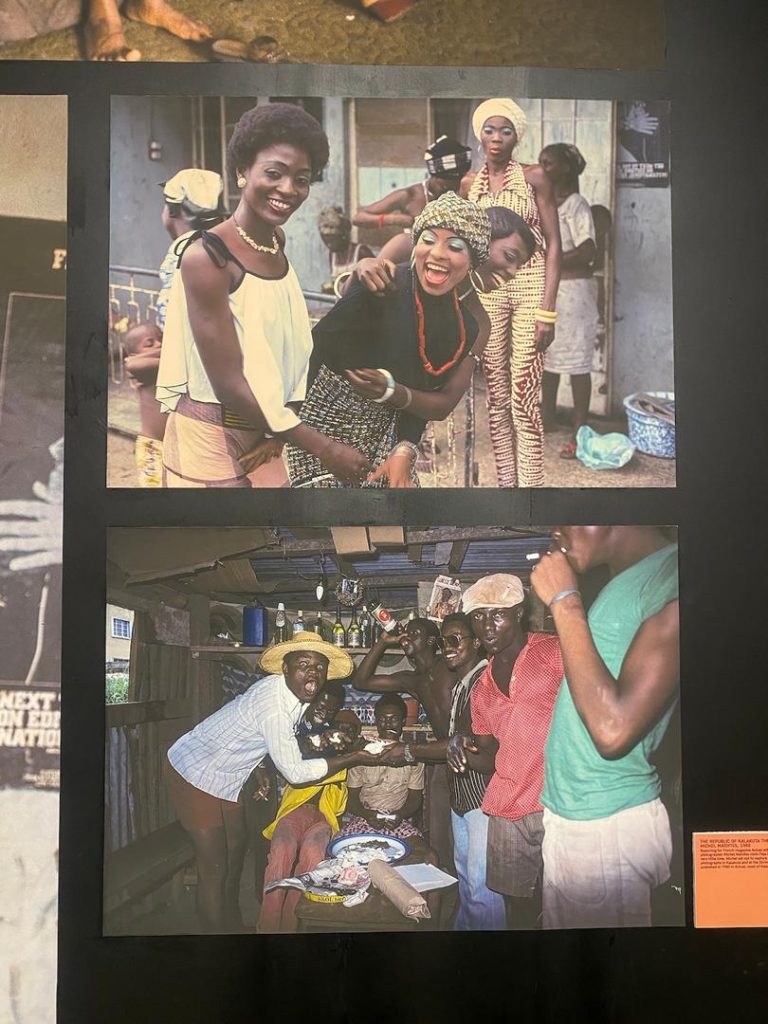

Fela’s band also included women who served as backup singers and dancers. These ladies, all of whom chose to join the band on their own, were referred to as Fela’s “Queens”. In a bid to form a case against him, the government falsely accused him of kidnapping these girls, and a number of them were brutalised during the 1977 raid. After the raid, they stood by Fela, and he married 27 of them in a single ceremony. This act has continued to fascinate many.

The Queens were also ahead of their time in the fashion scene with their use of brightly coloured makeup, intricate beaded braids, and elaborate headwraps.

It’s not difficult to imagine that these ladies were termed ‘eccentric’ because of their fashion choices at the time. Bright eyeshadow, thinly drawn brows, and face paintings with white chalks all serve as markers of alternative fashion. These were the Alté queens of Fela’s republic.

Read more about the fetishisation of Alté women.

TEACHER DON’T TEACH ME NONSENSE

Journeying along the exhibition, we see that Fela’s story is not neat; Afrobreat Rebellion doesn’t attempt to sanitise it. Instead, the exhibition highlights to us how his activism, flaws, charisma, and contradictions coexisted. In presenting historical personalities, it is tempting to portray them as saints and erase the actual history. Watching children ask questions and young adults curate their experiences, I’m reminded of Fela’s insistence in Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense: knowledge matters. This is where the exhibition shines–it functions both as an archive and a corrective by presenting the fuller, messier, historical version of him. Afrobeat Rebellion restores accuracy and depth for younger audiences who mostly encounter Fela through surface-level cultural references or hearsay in a city where he lived most of his life.