I shot my husband because I was bored. A statement which has no pleas for defence nor understanding. It upsets your moral perception of me, so confirmation bias has you distort the sentence to explain it away. My husband must have been a bad person, or I must be having an episode of an undiagnosed mental illness. Though I am fictional, this is a crime I could not have committed; you relate to me, and this you cannot do. But I still did it, and you are allowed to hate the story. However, the question of whether the story should not exist because it disrupts your illusion of relatability still stands. Why must art be relatable to you? Especially if you know so little about its origins.

THERE’S MORE TO LIFE THAN RELATABILITY

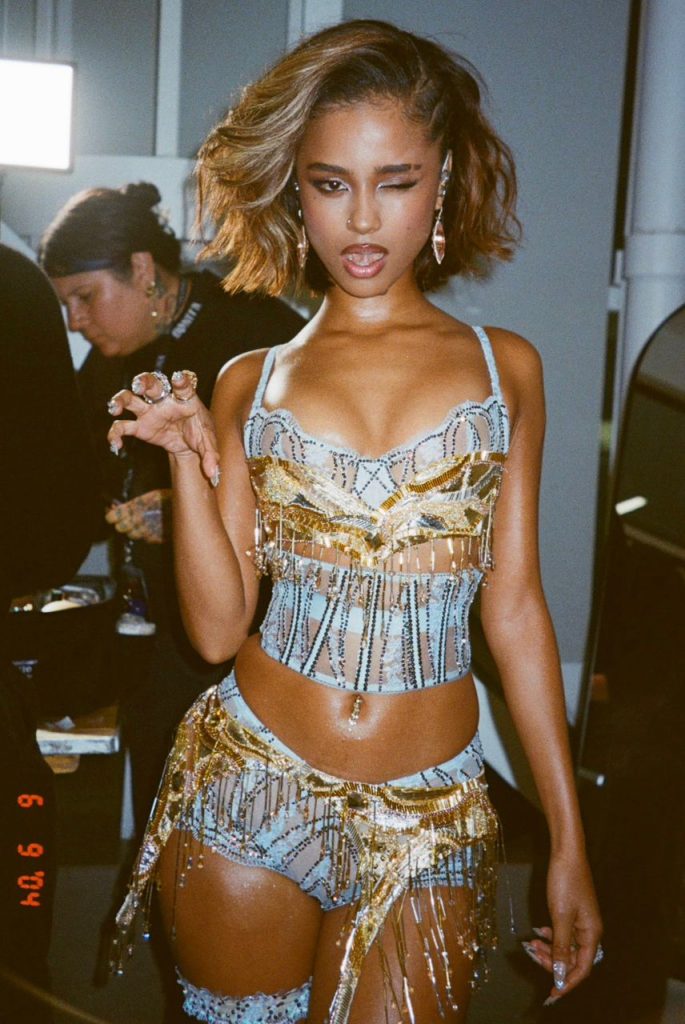

She whines her waist, sings, and laughs every time a camera is in her face– she is just like you. In the same breath, she insists on distinguishing between Amapiano and Afrobeats, has an unfamiliarly complex cultural background, and a Grammy – she is uppity. Of course, she’s Tyla, and if she never won an award or got a Vogue cover, she’d be the underrated African star people are sleeping on. It is an interesting paradox, the current social market demands, where one must be apologetic for success, a la Billie Eilish.

Eilish has spent most of her career expressing a sense of gloom surrounding every award win. Notably, after headlining Coachella, she joked, “Sorry I’m not Beyoncé!” The wunderkind became the youngest double-Oscar winner in history, with her song, “What Was I Made For?” A song whose video made a nod to her 2020 Grammy sweep, where she took home five awards. Despite being only 18 at the time, Eilish was subjected to inhumane levels of disparagement. Rarely did anyone critically discuss whether the music was deserving, and the backlash focused more on her. Tyla has faced similar critiques.

There are thousands of TikToks discussing Tyla’s ineligibility for a Grammy seldom mention the category, the other nominees, or the music. The discourse never discredits ‘Water’ as the best African performance nominee of the year, but Tyla is not eligible solely because she is new in the industry. However, so was her strongest contender in that category. The discourse constantly highlights a disconnect; that the story of an African rising to fame at the dawn of African dance music’s popularity is not relatable. So if she must take up space, she must be apologetic for doing so.

It is not a story you like or can relate to; one could argue it is unfair. But it is the tale, nevertheless. Similarly, in her “Dare to Dream” documentary, Ayra Starr expresses a similar sentiment. She understands that many things aligned to make her who she is today; timing being pivotal. She has always seen herself as a celestial being and believes the phrase “Grammy-nominated” suits her. It evokes a sense of national pride to make it this far, and she is not going to sell herself short. This narrative arc belongs entirely to her, and we, the listeners, are invited to witness her journey, not to insert ourselves into it.

Both stars are benefiting from the current Afrobeats takeover, but neither has relatability at the forefront of their appeal. This is because their sole aim is to make their country proud, as Tyla said, you’ve never had a pretty girl from Jo’burg.

THE TOO DIFFERENT AFRICAN:

The obsession with a starlet whom one relates to also plagues the African audience. However, while the West hopes for a faux-humble personality, Africans desire a somewhat non-alternative one.

It is February 2021, and indie filmmaker Korty EO has a guest on her YouTube series. The video is captioned, “I met the craziest girl in Lagos, she wasn’t so crazy.” The guest is none other than the multi-hyphenate Ashley Okoli. Vogue describes Okoli as the woman who defines Lagos’ coolest subculture, but Korty EO, vox populi, expressed the Nigerian sentiment… this is crazy.

As Alté is to every Nigerian subculture, so is crazy to anything expressive. The reason lies in the complex interplay of cultural values, religious beliefs, and post-colonial identities. The perception of alternative girls is not a monolithic phenomenon nationwide, but rather a nuanced reaction rooted in specific societal structures and contexts.

“Do you think you are a crazy person?” Eo asks, “I just think I am expressive,” Okoli said.

African cultures are founded on principles of community, communal identity, and respect for established norms. The aesthetic of alternative subcultures is an act of extreme individualism that challenges these communal bonds. In societies where one’s identity is inextricably linked to their family and ethnic group, this is seen on TikTok, where people explain that you can tell a person’s tribe by their personality. Of course, these are covert stereotype biases, but for many, their ethnic group is tied to their self. So a style that intentionally sets one apart from the collective can be interpreted as a rejection of their heritage. An expression of disconnection, or even an adoption of foreign values that are antithetical to the cultural fabric, rather than a valid form of personal expression. To do so is simply crazy.

Okoli raises eyebrows now and then, but her consistency has made the general public accept that this is her. However, Kenyan comedian Elsa Majimbo has begun her long journey. Majimbo socials are full of outfits, catwalks, and artistically edited pictures, think indie sleaze. It is far from how she was introduced—on her bed, with unkempt hair, in shades. The “first” Majimbo made jokes about wanting to be rich. The “new” Majimbo explores her visual presentation, career options, and content, as any other young adult would. If they could afford to do so, but they can’t, and that’s a problem. The Majimbo became viral because they saw themselves in her; it no longer exists, and while they could wait and watch the story unfold to see her next steps, everyone is obsessing over the loss of the relatable.

THE WORLD IS WIDE ENOUGH FOR MORE THAN OUR RELATABILITY:

In a 2019 The New York Times article, Jeremy D. Larson writes, “Relatability is the chief psychological lubricant that glides you thoughtlessly down the curated, endless scroll of your feed.” In the piece, Larson notes how politicians now use social media to appear more “normal” and relatable to voters, from live-streaming mundane activities to tweeting with emojis. He credits BuzzFeed co-founder Jonah Peretti with popularising the concept of relatability as a key to creating viral content. The content is designed to be so familiar and straightforward that people feel compelled to share it as a reflection of their own identity.

Politicians and brands adopted this strategy as an attempt to humanise themselves. As the Hamilton plays singing about Aaron Burr put it, “Like you can grab a beer with him.” His duel with Alexander Hamilton shattered that illusion, because ultimately, he is person, not thing.

The parasocial nature of the celebrity makes it harder to forget that they are not entirely a product, and relating to you is not always the point. Self-expression and artistry are as human as wanting to create something familiar. This insistence on relatability in art and entertainers takes away the space for spectacle and discovery. So maybe your morals don’t think I should shoot my husband. But was that the aim of the story?